Texas independence can be viewed from three perspectives: as an event, a historical period, and a political movement. The event is the brief war with Mexico by which Texas won its independence, and the historical period is the ten years of its existence as a sovereign republic. Texas independence is also a vocal and growing movement of Texans who favor secession from the United States and restoration of the Republic of Texas.

An American Colony in Northern Mexico

The “colonial period” of Texas history began in 1821 and lasted fifteen years. Moses Austin received Mexican governmental authorization to bring 300 American families into the Tejas region of northern Mexico.

The settlers would receive large grants of land if they were willing to pledge loyalty to the Mexican government, adopt the Spanish language, and convert to Roman Catholicism. Moses Austin died soon after getting the land grants, and his son Stephen took up the mantle as a promoter of American migration into Tejas.

As the number of American settlers grew, the Mexican government began to recognize its error and took several belated steps to try to reassert its authority in the region. In 1831, it abolished slavery.

This angered the American settlers, many of whom were slave owners, even though abolition was never effectively enforced. Later, Mexico abolished immigration and imposed high tariffs on imported goods, in the attempt to weaken or sever ties between the settlers of Tejas and the United States.

These measures served only to inflame the resentment of the settlers, who now called themselves “Texians,” toward the Mexican government.

The War for Texas Independence

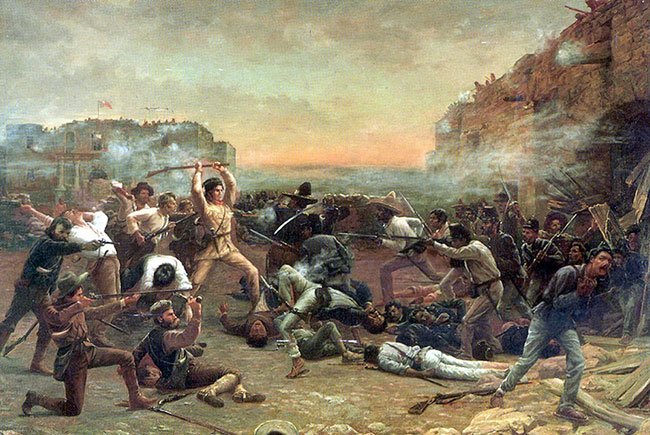

Overt hostilities began on October 2, 1835, when Mexican soldiers tried to seize a cannon from the town of Gonzales and were repulsed by the local citizens. In December, a band of rebellious settlers occupied the old Mission San Antonio de Valero, better known as “the Alamo,” and the president of Mexico, Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, decided to make an example of these upstarts.

Santa Anna marched against the Alamo with a force of about 1,800 soldiers. After a 13-day siege, the Mexicans succeeded in taking the position. All the defenders of the Alamo, numbering just under 200 men, died in battle or were executed by their captors.

Later in March, another Mexican army engaged a force of over 300 Texians near Goliad and forced their surrender. The prisoners were later executed on Santa Anna’s orders.

The massacres at the Alamo and Goliad served to unite the Texians in a lust for vengeance. On April 21, 1836, a force of roughly 950 Texians under Gen. Sam Houston surprised and routed Santa Anna’s army in the Battle of San Jacinto.

Alamo – Now

1847 watercolor of The Alamo in San Antonio

The victorious Texians captured Santa Anna after the battle but later released him in exchange for his recognition of Texas as an independent republic. The border between Mexico and Texas was fixed at the Rio Grande.

The war for Texas independence had lasted less than seven months, but the real struggle was only beginning. Declaring and winning independence would prove less difficult than being independent.

The Republic of Texas, 1836-1846

During its ten years of sovereignty, the Republic of Texas confronted several problems which will sound all too familiar to the contemporary American reader.

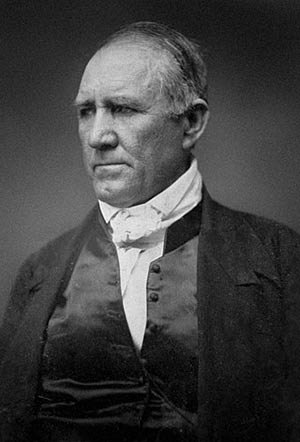

Polarization of political debate was in evidence from the beginning and intensified as time progressed. Though formal political parties never developed in the Republic, two factions quickly emerged. Proponents of annexation, led by Sam Houston, supported annexing Texas to the United States and peace with the Native American tribes.

The nationalist faction, led by Mirabeau B. Lamar, supported the continued independence of the Republic and its expansion to the Pacific Ocean, as well as expelling the Native American tribes. Public opinion strongly favored annexation, and Sam Houston became the first president of the Republic on that platform on September 5, 1836.

National defense was an immediate and urgent priority for the Republic. Shortly after the Battle of San Jacinto, the Mexican Congress had renounced Santa Anna and the Treaties of Velasco and ordered the continuation of hostilities with the Texians.

While no coordinated Mexican military action against Texas took place until 1842, Mexico successfully waged a “cold war” to keep the Texas frontier in a constant state of agitation throughout much of its existence.

The war on terror is an apt description of the Republic’s relations with its indigenous Native American populations during and after the Lamar administration. President Houston had negotiated peace with the various tribes, and during his first term in office, they had remained fairly quiet.

Lamar succeeded Houston as president in December of 1838. He immediately began a drive to expel the Cherokees from the Texian territory, justifying this action on his belief that the Cherokees were collaborating with the Mexicans to stir up trouble.

Preemptive strikes into Comanche territory provoked retaliatory raids which continued throughout Lamar’s presidency. Houston succeeded Lamar in December 1841, and by the end of his second term had managed once again to make peace with most of the tribes.

Deficit spending characterized the Republic’s fiscal policy from the beginning. When Houston began his first term, his administration inherited a national debt of $1.25 million from the interim government of David G. Burnet. When Lamar took office, the debt was $3.25 million. Lamar’s expansionist and aggressive policies added nearly $4.9 million to the debt. In his second term, Houston and the Congress saw clearly the need to economize but never succeeded in balancing the budget.

When Texas became part of the Union, the Republic’s national debt had swollen to roughly $12 million. Had the United States not annexed Texas and assumed its debt, it’s doubtful whether this debt could ever have been retired.

A CAPSULE SUMMARY OF THE PRO-INDEPENDENCE VIEW

Today’s Movement to Reestablish Texas Independence

The nationalist political sentiments of Mirabeau B. Lamar and his supporters have never died out. There are some even today who would assert that Texas’ petition for annexation into the United States in 1845 was a serious mistake.

More common are those who think the federal government is in contempt of the United States Constitution, and that Texas should, therefore, withdraw from the Union and go its own way in the world.

A typical expression of current Texas secessionist views is in the language of the following petition.

“WE PETITION THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION TO:

Peacefully grant the State of Texas to withdraw from the United States of America and create its own NEW government.

The US continues to suffer economic difficulties stemming from the federal government’s neglect to reform domestic and foreign spending. The citizens of the US suffer from blatant abuses of their rights such as the NDAA, the TSA, etc.

Given that the state of Texas maintains a balanced budget and is the 15th largest economy in the world, it is practically feasible for Texas to withdraw from the union, and to do so would protect it’s (sic) citizens’ standard of living and re-secure their rights and liberties in accordance with the original ideas and beliefs of our founding fathers which are no longer being reflected by the federal government.”

At this writing, 119,063 people have attached electronic signatures to this petition, which testifies to the growing popularity of the modern Texas independence movement. While it’s not our purpose here to argue the merits of the idea, it’s fitting to note these lessons from history.

- During its time as an independent republic, Texas struggled with many of the same problems the federal government confronts today, with only limited success.

- Texas has seceded twice before, once from Mexico to become independent, and once from the United States to join the Confederate States of America. Neither of those occasions worked out well in the long run.

- The long-term viability of any newly independent nation depends much on the unity of will and purpose of its citizens.

Do 21st-century Texians have the necessary unity of will and purpose to seek our independence once again? If so, one can only hope that we do a better job of it next time.